The Value of Water-An Assessment of a Direct Application of Ecosystem Service Conceptions

In this blog I will develop the discussion of Wetland

Ecosystems in Africa, whilst more directly combining this with Ecosystem

Service conceptions. This will be through looking at an academic paper which

uses valuation techniques to discuss irrigation projects, showing how the

concept can be applied in an African development context. Further, it

highlights some of the limitations and counter-arguments discussed in an

earlier blog.

In ‘The Value of Water’ Barbier and Thompson combine

hydrological models and economic valuations to predict the likely opportunity

cost of upstream damming and irrigation on the downstream net benefits, within

the Hadejia-Jama'are River Basin in north-eastern Nigeria. This is particularly

interesting in light of recognition of importance of wetlands, a stance which their results support.

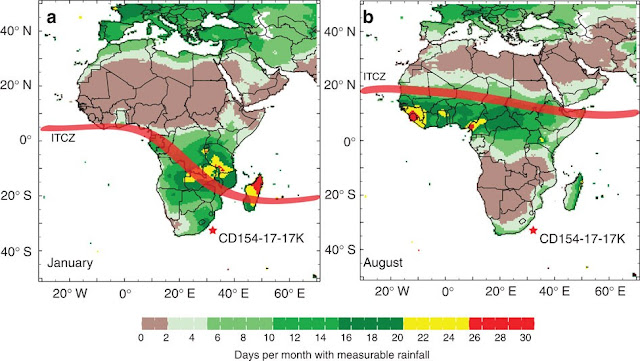

| Figure 1-Hadejia-Jama'are Basin |

They find that the reduction in floodplain areas from many

of these schemes lead to the loss of direct use values that local populations gain, crop production, fuelwood and fishing. They find that these often outweigh the benefits from planned or implemented irrigated agriculture upstream, with values both per hectare and per metre cubed of

water significantly less in irrigated areas than in the floodplains they reduce. For example in the Hadejia-Jama'are

wetlands net present values for above direct uses found to be around $34-51 per

Ha and $10-15 per 10m3 of floodwater, whilst in the Kano River

Irrigation Project the agricultural production benefits are only $20-31 per Ha,

or $0.03-0.04 per 10m3. This means that many of the schemes overlook

the importance of floodplain benefits, utilising the water in irrigation

schemes without the economic output of floodplain areas. This can be seen as

highlighting the usefulness of ecosystem services as a method of guiding

development policy and techniques.

However, the flaws in the paper also highlight some of

the issues in ecosystem services and their underlying logic. Firstly, its

economic valuation methodology is somewhat limited, focusing solely on direct

use values, both for the irrigation areas as well as the floodplains. This

means that a huge range of other human economic uses are not included. In the floodplain

areas aspects such as the seasonal role as pasture, scarcity mitigation and

tourism, whilst the importance of the water for drinking, sanitation and

industry are mentioned but not modeled for upstream usage. The importance of

these sources is undeniably hard to quantify. For example the impacts of water

on health are dependent on a range of factors beyond total volume provided,

such as whether piped supplies are standing pumps or in-home, individuals levels

of education and waiting times, and so perhaps can never be expect to be adequately

quantified.

Beyond this, the focus is purely on human usages of the water

resources, and overlooks the natural and environmental importance of the river.

Again, although there are brief mentions of the floodplains importance to

migratory birds, this isn’t factored into valuations, and shows the

anthropocentric focus of the valuation, as is the case with many such

valuations. Further, it also highlights the importance of complexity in these

valuations, which are often hard to achieve.

Despite these criticisms, the paper offers an important

stance in showing the need to recognise the downstream impacts of schemes. It

illustrates many of the arguments made in Schroter et al on the role ES

concepts are best placed to play, advising and guiding policy, with its

limitations accepted but nonetheless utilised to help inform decisions.